Bitter rot is a fungus disease that causes fruit rot during the summer and preharvest period. The bitter rot fungi are almost worldwide in distribution and cause an especially important economic disease in the southern areas of the United States. Outbreaks can occur rapidly, and losses can be severe, especially under prolonged warm, wet weather. Several host species can be affected. On peach and nectarine, the same fungus causes a disease known as anthracnose, and on grape it causes ripe rot. The primary hosts, however, are apple and pear. The canker phase of the disease is rare; therefore, the discussion below is limited to fruit infection.

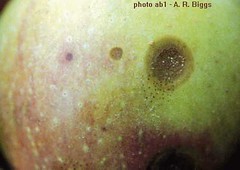

| Figure 1. A few small bitter rot lesions with colored acervuli appearing on the surface of the larger lesion. The black dots are fly speck disease. Photo: Alan R. Biggs, West Virginia University. |

|---|

|

The disease occurs in orchard blocks beginning in July through August; however, its appearance varies with the climatic conditions during any particular season. Fruit infection can occur early in the season, but symptoms do not develop until the fruit begins to mature. The rot begins as a small, light brown, circular lesion. As lesions enlarge, they change to a dark brown and form sunken or saucer-shaped depressions. The number of lesions per fruit may vary from one to many. When lesions reach about 1 inch in diameter, fruiting bodies of the fungus appear near the center of the lesion. Under humid conditions, large numbers of spores are produced in a creamy mass, salmon pink in color (figs. 1, 2), which are often arranged in concentric circles. Under dry conditions, the spore mass appears crystalline. The rotted flesh beneath the surface of the lesion is watery, appearing in a V-shaped pattern in cross section that narrows toward the core (fig. 3). The fruit decays rapidly as it ripens and eventually shrivels into a mummy that may remain attached to the tree throughout the winter.

| Figure 2. Older and larger bitter rot lesion than that in fig. 1 with the surface covered with acervuli. Photo: Kenneth D. Hickey, Penn State University. |

|---|

|

The fungus overwinters in mummified fruit, in cracks and crevices in bark, and in cankers produced by the bitter rot fungus or by other diseases, such as fire blight. Jagged edges of broken limbs are also ideal sites. The bitter rot fungus is one of the few rot organisms that can penetrate unbroken skin of fruit. Although penetration is direct, wounds can be colonized rapidly by the fungus. Spores are waterborne and are released during rainfall throughout the growing season. Fruit infection can occur early but is more common from mid to late season. Often, the first infections appear in cone-shaped areas within the tree beneath mummies or a canker. Factors that determine the time of appearance of bitter rot are the maturity of fruit, temperature and humidity, and the presence of disease in the area. The optimum conditions for disease development include rainfall, relative humidity of 80% to 100%, and warm temperatures. Infection can occur in as little as 5 hours at 79°F.

| Figure 3. Characteristic V-shaped discoloration is typical of bitter rot. Photo: James W. Travis, Penn State University. |

|---|

|

Application of fungicides on a 10- to 14-day schedule from petal fall through harvest is the most effective means for disease control. More frequent applications may be necessary under conditions favorable for disease development. Some cultural practices may help reduce inoculum and thus reduce the incidence of the disease. Cultural practices include removing mummified fruit, dead wood, and fire-blighted twigs from trees and removing newly infected fruit during the growing season. Although apple cultivars do not vary widely in their susceptibility, the disease is often more severe on ‘Empire’, ‘Freedom’, ‘Golden Delicious’, ‘Fuji’, ‘Granny Smith’, and ‘Arkansas Black’.

See Table of Apple Cultivar Susceptibility to Bitter Rot for more information.

Resource

http://www.caf.wvu.edu/kearneysville/disease_descriptions/ombitter.html

Adapted by Alan R. Biggs, West Virginia University

Prepared by K. S. Yoder and A. R. Biggs from personal observations and the following source:

A Grower’s Guide to Apple Insects and Diseases in the Southeast. 1993. Alabama Cooperative Extension Service, Auburn University, Circular ANR-838. Ed. J. R. McVay, J. F. Walgenbach, E. J. Sikora, and T. B. Sutton.

Original text prepared by A. R. Biggs, J. W. Travis, and J. L. Rytter. The original version of this article appeared in The Mid-Atlantic Orchard Monitoring Guide (NRAES-75) and is reproduced with permission from the Natural Resource, Agriculture, and Engineering Service, Cooperative Extension, 152 Riley-Robb Hall, Ithaca, New York 14853-5701, U.S.A. (607) 255-7654.